Evaluating the credibility of a source is one of the most important things you’ll do when researching for your writing topic. After all, bad sources can lead to poor reasoning and shoddy argumentation, both of which can hurt your business, career, or reputation.

“Gosh, I know Bob can never get his facts right, but the man knows how to wield a participle phrase,” is not really thing you want people saying about you. Unless your goal is to see how many fights you can start on Facebook with eloquent but incorrect information, I guess?

Most of us, however, simply can’t hope stunning syntax will make up for just being wrong a lot. Instead, we need to employ accurate sources as part of our writing process to ensure we’re producing credible content.

So, how does one go about verifying source credibility, especially in the Internet Age? I’ve got 4 strategies for you to use to check the veracity of your information. I recommend applying of them to every source you use for maximum (but not perfect) effectiveness.

But First: What is a Source?

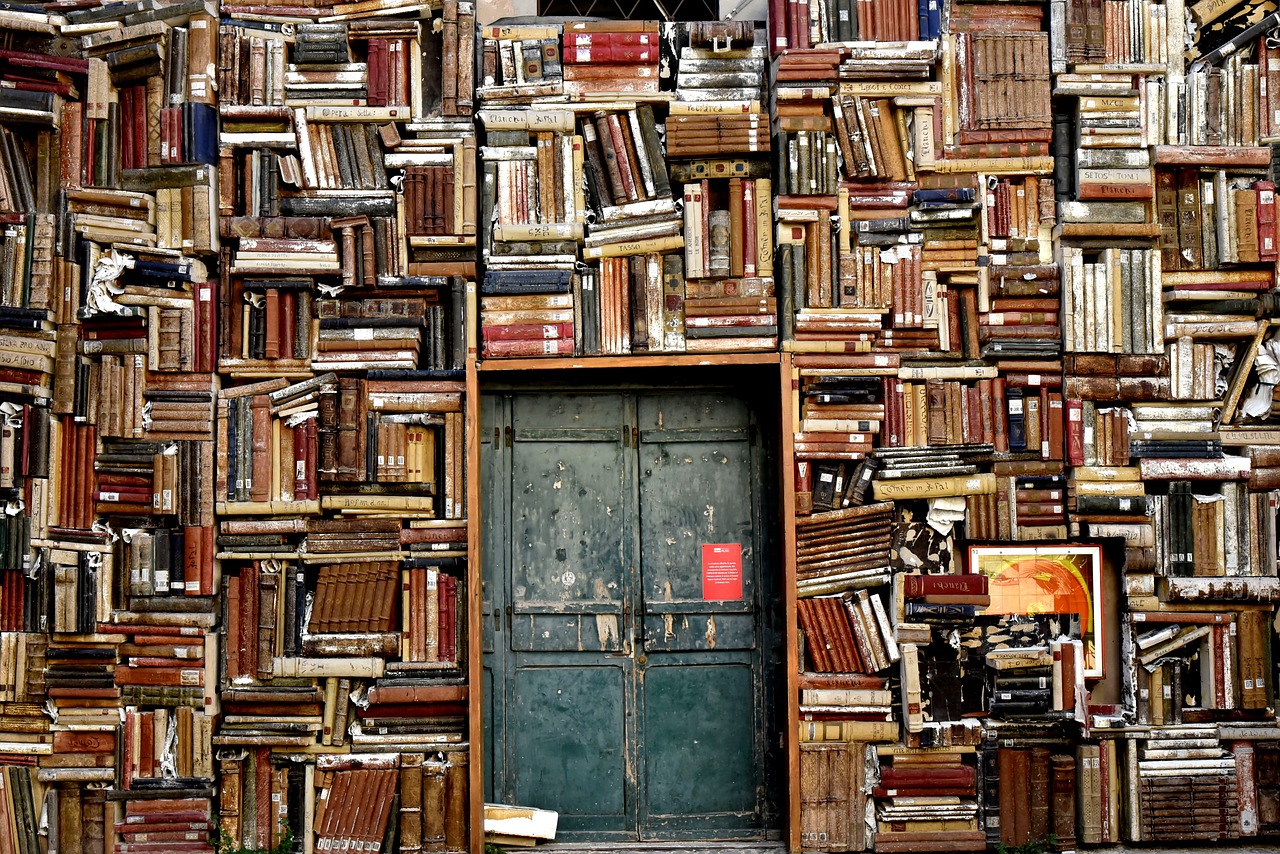

Most simply, sources are where we get information, and they can be documents, electronic materials, humans, photographs, and so on. Basically, if it’s something that gives you data, it can be a source.

We typically classify sources as primary, secondary, or tertiary.

- Primary sources are materials produced contemporaneously (e.g. court records).

- Secondary sources are materials that describe or evaluate primary sources (e.g. books).

- Tertiary sources are materials used to organize or locate primary and secondary sources (e.g. library catalog).

The sort of writing you’re doing will affect the kind of sources you need, but the 4 strategies of source evaluation can be applied to all 3 source varieties.

Evaluation Strategy 1: Examine the Publisher.

The person, group, or institution publishing something provides valuable details about how likely your source is to have credible information.

Academic, government, and major media organizations all tend to require authors to meet certain levels of accuracy in order to be published. Scholarly sources in particular go through something called “peer review,” which means a paper or article had to be verified as reliable by subject matter experts.

Now, keep in mind, even the most lauded or prestigious publishers will make mistakes in effectively carrying out standards of accuracy, which is why I recommend using all 4 strategies. But. The sorts of organizations that need to maintain their reputations will more vigilant about what and who they’re publishing.

Evaluation Strategy 2: Consider the Author’s Credentials.

The person, group, or organization that writes the source is also going to impact how reliable the source is.

Individuals who have formal training and education and/or extensive, real-world experience are probably going to produce more reliable information than someone who dabbles in a topic on the weekend.

Some things you can check when evaluating the author include past publications, work history and current occupation, or professional associations. Essentially, is this person an expert on what they’re writing about?

For organizations, check their industry-wide reputation, how long they’ve been publishing materials, and whether they provide names or contact information related to the source. Or, in other words, does this group have a good track record on this particular topic?

Evaluation Strategy 3: Review the Publication Date.

The more recent the publication, the more likely the information will be up to date in terms of research or current best practices in a field. That’s not to say older sources of information won’t be reliable or that they should be eschewed in favor of newer sources.

Certainly not. You’ll simply want to confirm that the data is still relevant and hasn’t been replaced by more recent discoveries or attitude shifts.

Evaluation Strategy 4: Cross-check the Source’s Information.

Two sources saying the same thing is better than one, three sources saying the same thing is better than two, and so on. The more agreement you find about facts and details across multiple sources, the more likely the information you’re examining is accurate.

What to do if the reported facts seem to be mixed, i.e., one sources says this while another says that? I tend to recommend going with the what seems most widely accepted but including a note in your writing to let your readers know the situation.

However, be careful about playing the “false equivalency” game You know the one where someone ascribes equal weight to totally unequal sources? We see this nightmare happen all too often with topics such as climate change.

“While most climate scientists agree that climate change is happening and is bad, the debate remains unsettled as there are several people on Twitter who insist the whole thing’s a hoax.”

Don’t do that. The insistently opinionated disagreeing with thousands of educated, experienced researchers is not a legitimate discrepancy.

Speaking of which….

Accurate Information vs. Biased Information

The strategies I’ve discussed here are intended to help you locate and use sources that tend to be accurate. Please note, though, that accurate does not preclude bias.

I’ll deal with the challenges of bias in more detail with a subsequent post, but for now, I’m going to give you one quick and dirty trick for assessing whether a source is biased.

You ready? Here it is:

Step 1. Ask yourself “Is this source biased?”

Step 2. Respond with “Yes.”

And that’s it. Dr. Bond’s patented (not really) method of determining if a source is biased. Plus! I guarantee this approach will work every time too. Why?

Because all sources are biased; it’s just a matter of determining the degree and what sort of influence the bias had on the formation and distribution of the information.

More to Come!

Join me later this week as we frolic together in the wild fields of writing. In the meantime, follow me on Twitter!